Tyler Cowen, one of the intellectual forefathers of the Progress Studies community, believes that we should do nearly everything within society’s capacity to increase GDP, erm, I mean progress. This is supported by Tyler’s moral framework, where he applies no discount rate to future human lives and, as such, believes nearly all moral value lies in the far future. To the extent that progress today can make many more lives in the future better off, as long as we don’t get in our own way (i.e., existential risk, societal collapse), maximizing progress for long-term gain should be the priority.

While I strongly disagree with Tyler, I at least respect the view because it comes from a bona fide belief derived from a different moral framework than the one I hold.

One of the other intellectual forefathers and leaders of the Progress Studies community is Jason Crawford, who recently argued that I, personally, should want a larger human population (without specifying how much larger, and where these people should be born into). In this essay, Jason makes the argument that essentially, more people lead to more progress and better matching opportunities. Jason claims the outcome of having a larger population, as a result of having more progress and better matching, is better for individuals but is silent on the mechanism by which it does this.

Despite Jason seeming to hold the same moral framework as me (valuing current humans more than future humans), Jason’s views resonate with me even less than Tyler’s.

To me, I care deeply about progress because it can make it easier for our society to enhance (extant) human flourishing. In this framing, progress is merely a tool, not an end in itself. Often, when I read/interact with people in the Progress Studies community (and Jason is just being used as a personification of this trend), it seems that progress is both the means and the end.

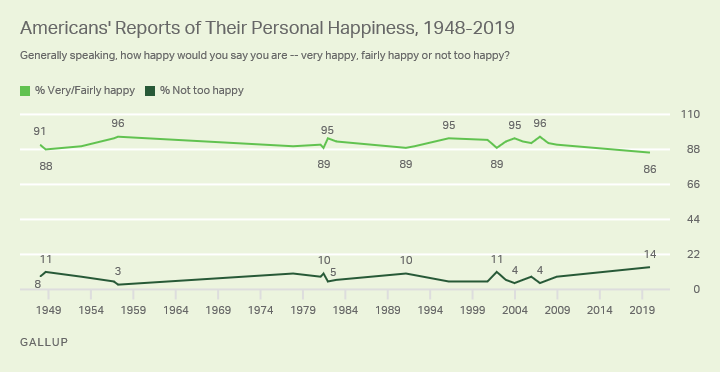

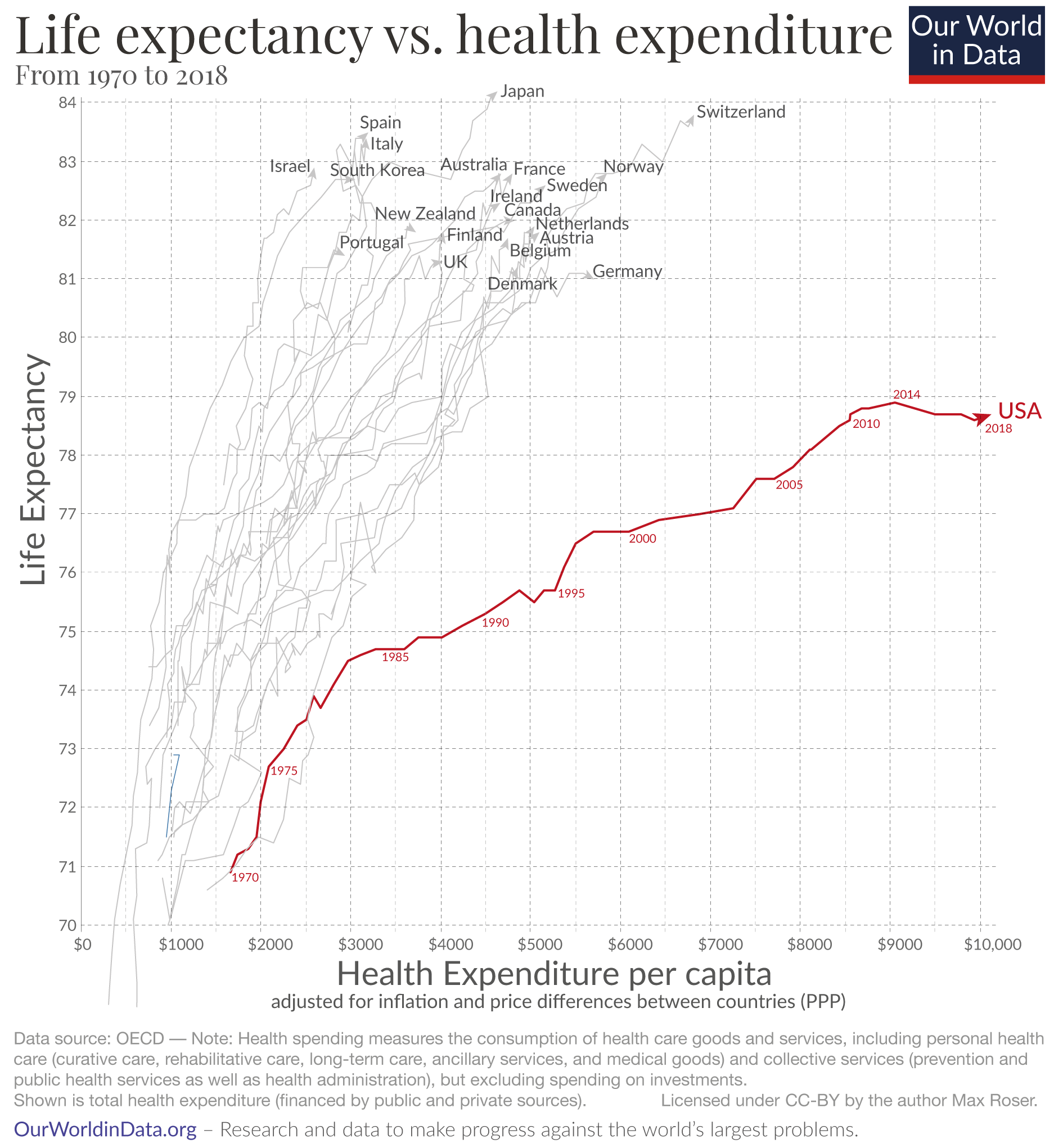

To use the USA as an example, a country that is not only rich but, relative to other nations, has grown its wealth at a much higher rate; it doesn’t seem like this wealth, let alone the increase in wealth, is doing a great job at enriching well-being. This is evident either in the conventional sense of people’s self-reported happiness or in the more utilitarian sense of people not living longer.

In terms of increasing human flourishing for those alive today, increasing progress is just one, among many tools, and certainly not the one with the most low-hanging fruit, ways to increase well-being.

Because of this, I feel icky when people treat progress as a normative concern rather than a tool (albeit, a very good one), especially when it evokes a series of societal changes that seem likely to both increase societal fragility and decrease well-being. We should focus on progress, to the extent it helps us achieve our broader goals; we should not focus on progress to the extent it makes our broader goals harder to achieve.

I appreciate Jason is just one voice, but from engaging with this community online and offline for several years now, this viewpoint is something I encounter quite frequently.

As a parting note, I wanted to include this excerpt from a Joseph Heath blog post:

“In my view, the biggest “political economy” discovery of the 20th century is that you can increase the wealth of the population by a factor of eight or nine times, and not have it reduce the level of possessiveness, or of resistance to redistribution, by one iota. This never ceases to amaze me (much as it would have amazed Karl Marx, who just assumed that once people were rich beyond the dreams of avarice – which at least 95% of us are, by the standards of the 19th century – that we would become less preoccupied with “mine” and “thine”).

Even during my own lifetime, GDP per capita in this country has more than doubled. My children are growing up in the country where the average person is twice as wealthy as the average person was when I was their age. (And that’s not even taking into consideration technological change.) Yet there is no discernible change at all in how people feel about their financial situation, or their consumption. The suggestion that we might want to have a carbon tax to combat global warming, or a road toll to reduce congestion, or even just a more progressive income tax to help the poor, is met with howls of outrage. We are told that hard-working Canadian families are just taxed out, they can’t possibly shoulder these additional burdens. Apparently there are just so many other bills to be paid, there is no room at all to solve these pressing social problems.

Now I happen to believe that this is actually how most people honestly feel. It’s not just a made-up thing. The average Canadian family does feel financially pressed. The question then is how it could be, given that these hard-working families are approximately twice as wealthy, on average, as families were when I was young. How is it possible to double the wealth, and yet not create any slack?

(And don’t say it’s because median incomes are stagnant, the 1 per cent have taken it all, etc. This is Canada, not the U.S. — the income trends are different. Plus anyone who’s been in an average suburban home of late knows full well that people have a pretty elevated consumption level. Just take a look at that house above, which is being sold to people probably in the upper 60-80% income range, definitely not upper 10%.)

The answer is that people are stuck in a race to the bottom, involving various forms of (implicit or explicit) competitive consumption. House size is one of them. Houses just keep getting bigger and bigger. (In Luxury Fever, Robert Frank cites the factoid that the bottom income quintile in the United States enjoys the same amount of living space as the average European.) I recall once asking one of my in-laws, who had just bought a new suburban home, which model she had chosen. “The biggest one,” she said. I love that answer. It’s one thing to buy the biggest one, but to buy it under that description is just awesome. Let the race to the bottom begin!”

I very much agree with this take, and you have named a lot of places where my idea of “progress” does not align with the “progress studies” movement. Jason’s idea that we should have more kids so we can have more genius people with better technology and slightly better jobs with slightly more aligned friends seems to be missing the point that we already have all of that and are still missing the human flourishing part. We don’t need more, we need better distributed. We need more meaning. The human flourishing part is more important to me than progress for progress sake!